News

Made in England: Combating Racism 1969-75 - Chapter 8 - Made in England - The Memoirs of Dr Choudry Mohammed Walayat MBE

Now that I was back in Sheffield, I made a conscious effort to get involved in the city, its intriguing politics and its powerful trade union movement. I was not going to be one of those Pakistanis who lived a quiet life, just getting on with my job, existing from day to day but with my head and mind still firmly focussed on Pakistan and just relying on the traditional ways of doing things. I re-joined the Labour Party as soon as we moved into our house in Darnall. Then when I got my job as a bus conductor, working for the City’s Transport Department, I joined the TGWU, the Transport and General Workers Union, the largest trade union in the U.K.

In those days in Sheffield the unions and the Labour Party, if not quite the same thing, had a very close symbiotic relationship and leading figures were often key people in both organisations. There was no problem about choosing to join the Labour Party, since they had not only consistently opposed racism in Britain but had attempted to make things better for newcomers like us by passing, for example, the 1968 Race Relations Act, which set up the Race Relations Board. That was only one step in the right direction, but the leadership of the Labour Movement in Sheffield clearly wanted to be supportive, even if they did not fully understand what they were dealing with. In 1966, even before the Race Relations Act, the City Council had established a Community Relations Committee chaired by Alderman Issy Lewis, a very senior Jewish member of the City Council. They appointed Syed Rasul, who came from East Pakistan (soon to be Bangladesh after the Indo-Pakistan War in 1971) as the first full-time Community Relations Officer ; he summarised his aims as;

1. To help immigrants integrate into the community. 2. To look into their problems and help them build a good and harmonious relationship with the people of the host community.

3. To build up a harmonious community in Sheffield with the people of various nationalities.

I could sign up to all those three points and, in fact, I was asked to join the Sheffield Community Relations Council in 1973. Later, I became its Deputy Chair and served in that capacity from 1979-84.

Not that all Labour voters were sympathetic to the new migrants who were now living in their midst in working class communities. In fact, they could be very racist, but in an essentially English way that usually just meant casual comments, sometimes delivered with real venom and conviction, but often in a more shamefaced way. Not infrequently there could be small incidents of violence, particularly from teenagers and young men. Usually it was nothing more than abuse being shouted out in the streets, but people were sometimes attacked and house and shop windows were smashed on occasions. In those days the Pakistani community tended to keep its head down, believing that to respond in kind would only worsen relations. They would not have such an attitude today. Many members of our community have witnessed some unpleasant behaviour over the years and they have been made to feel very unwelcome at times.

The Labour Party gets a new member

None of the Pakistani community would have looked to the Conservatives for support, even though Edward Heath, their Leader, had sacked Enoch Powell from the Shadow Cabinet for his “Rivers of Blood” speech. It was still clear that the moral heartland of the national Conservative Party was still flirting with racism to some degree. As for the Liberals, they barely existed in Sheffield in the early Seventies and therefore they were off the political radar for the moment.

Joining the Labour Party now meant going along to meetings at the Labour Hall on Balfour Road. This was a former army hut that the Labour Party had bought many years before and set up as their headquarters in Darnall. This was the domain of one of Sheffield’s Labour legends, the larger than life Alderman Sidney Dyson, a dominant figure on the Council and once the much respected Chairman of the Transport Committee – where, in effect, he had been my employer. He was a huge personality who was the Labour Party to most voters in the east end of Sheffield and I soon realised that I had landed among some of the most influential people in Sheffield politics. I got to know Patrick Duffy, the local MP for the Attercliffe Constituency, who looked to me for advice on immigration issues, and he has remained a firm friend of mine ever since.

The younger Darnall councillors included Frank Prince, who later became Lord Mayor, and John Cornwell, who would go on to become the Deputy Leader of the South Yorkshire County Council. They were keen to have a member of the Pakistani community join them because they had no idea of how we lived, our problems and issues, and what we were hoping for when we came to Britain. Yet I always felt they wanted to help. Even Harry Firth, a councillor who was a genuine community representative and lived in a back street off Staniforth Road, who had not been very welcoming to the Pakistani community initially, later came round and I found I could work with him, once he realised that our community, and especially its votes, was not in his pocket.

Active in my Union

At union meetings held at Transport House in Campo Lane, I came under the influence of Alderman Bill Owen, District Secretary of the TGWU, Chairman of the Trades and Labour Council and an influential City Councillor as well. He encouraged me to become a member of a number of official bodies that he knew needed representation from the Asian community. He could arrange these things and so therefore in 1971 I became a member of the North Sheffield Health Council, where one of my colleagues was the young rising star, Clive Betts, later Leader of the City Council and M.P. for Attercliffe. Once on the Health Council one of the first initiatives I proposed was the introduction of Halal meat in the hospitals, an issue that was very important to the Muslim community, and this was accepted.

I was also nominated to be a member of the Social Security Tribunal where I could give advice and guide decisions about the issues and problems of Pakistanis. They all wanted to work hard and send money home, but also found themselves at times unemployed or ill and in need of financial support from the state. My appointment was by the Secretary of State and it came after I had to endure a two-hour interview by a senior civil servant from Leeds. We sat as a panel of three, hearing appeals from people who believed they had been refused their entitlement to money for basic necessities, when they were in straitened financial circumstances.

Bill Owen, who among his many posts was Vice Chairman of the Education Committee, also arranged for me to be on the Governors of Greenland Primary School, which served the Darnall area and also Park House School on Bawtry Road where many Pakistani children went to secondary school. They preferred Park House and its sympathetic headteacher, Barry Winter, to Waltheof School which, although nearer, had a reputation for hostility between English and Pakistani children. So much so that at one time they were bussed home on separate buses. Park House was a school that served the Tinsley Area, where many families from Mirpur were now living and whose children went to that school. I later became the Deputy Chair of Governors and stayed on the governing body until the school closed in the Nineties.

Through these positions I got to know the next generation of leading figures in Sheffield politics, men who would be my colleagues on the City Council when I finally got elected in 1986. Howard Knight, later Chair of Finance, was the full time Secretary of the Health Council. At Trades Council meetings I made friends with Mike Bower, then the Father of the Chapel of the NUJ and working as a reporter on the Sheffield Telegraph. He would follow Clive Betts as the Leader of the Council in the Nineties when I represented Darnall Ward.

They were an impressive bunch: the new face of Labour, all graduates and all holding down middle class professional jobs. They were a different breed from the Sid Dysons and Bill Owens, yet they all managed to rub along together all right, unlike in some Labour councils. They would run a council in the early Eighties that would challenge the Conservative Government over its assault on Local Government, when Mrs. Thatcher attempted to squeeze the lifeblood out of local councils, leaving public squalor in her wake. These new, left of centre, graduate politicians were much more articulate about antiracism than their working class predecessors and they were keen to advance the cause of ethnic minorities within Sheffield.

The Communities begin to learn to live together

One such significant event happened in 1972, when Haji Mohammed Bostan, Chair of the Bodmin St. Mosque and a man with a worldwide reputation in the Muslim world, approached John Cornwell to see if he could get permission from the Council for the use of Coleridge Road playing fields for a great Islamic Congregation. The plan was to erect marquees on the football pitches and invite Muslims from all over Britain, even from abroad, to come to Sheffield for a weekend of prayer, discussion and fellowship. No one in the Muslim community was certain how the Sheffield City Council would react, or if the English residents on Coleridge Road and in the surrounding neighbourhood would object.

Permission was granted, the marquees were erected and over 6000 people came for the weekend. There was some interest from local people but no problems, while it demonstrated to the Asian population that official Sheffield was keen to help and that many ordinary English people were, at least, open minded about their new neighbours. I could understand their concerns. Suddenly, into their working class communities, had arrived people from another culture and another way of life and it would have been very strange if there had not been some tensions caused by this.

By 1972 there were 5,000 Muslims in Sheffield, from Pakistan and the new country of Bangladesh, and they were nearly all men. Most of us had come looking for work, mainly in the steel mills, although many of us had found jobs on the buses or as taxi drivers. Many did not speak very much English and they had different customs, including their shalwar kameez clothes, and lived in crowded rooms. This concerned their English neighbours, who were not used to the smell of curry or loud male conversations late into the night, often when they got home from a late shift. Inevitably there was prejudice about white girls going out with Asian men, whose own women were back in Pakistan, and, less seriously, English people were often irritated when Pakistani drivers would stop their cars in the middle of the road to have a chat with the driver of another parked car, as they would have done back home. Attercliffe, where many Pakistanis lived, was nicknamed “Little Pakistan” and this was not meant to be a compliment. Some English people muttered that they would lose their jobs to Asian workers and that “the Pakistanis are taking over!”, which really could not have been further from the truth when observed from the Pakistani perspective.

In Sheffield, the Pakistanis mainly came from Mirpur district and many knew each other from back home. They were Kashmiris from rural villages, had limited education and few had qualifications that would be recognised in England. Many would have found Jhelum, let alone Lahore or Karachi, unfamiliar and overwhelming, so, not surprisingly, they did not immediately fit into Sheffield society. They expected to be the last in the line for jobs and only be offered those that the English workers did not want.

Mirpur people were among the first Pakistanis to “find” Britain. Although a long way from the sea, there was a tradition among Mirpur men to go to sea, and many of these sailors, when they reached British ports jumped ship and stayed in the U.K. They in turn told people back home what advantages they could have in wages, education and health and so more peole from Mirpur followed. The first Mirpur man to come to Sheffield was Karam Dad who came to Yorkshire before the War, ran a shop in Attercliffe and then, in 1947, set up the Pakistan Muslim Welfare Association to help new migrants from Mirpur and to encourage others to come. There were jobs in the steel industry in the late Fifties and Mirpur men came to Sheffield because they had friends and relatives there. They were poor and unqualified in a strange land: not surprisingly they looked for familiar faces and stayed in their friends’ houses when they first arrived.

However, at the end of the day, two working class communities learned to live with one another and between them they have created a significant piece of Sheffield history. Here, in this southern corner of Yorkshire, an all-white city in the early Fifties became a multiracial one in the next quarter of a century. Thanks to the efforts of a lot of people they have got on reasonably harmoniously and I would like to think I had played my part in that important passage of local history.

Not that there were no unpleasant incidents and I didmy best to help resolve them. After one incident I contacted the new, national Race Relations Board and presented the case so forcibly before the Conciliation Committee that the Chair of the National Board, Sir Geoffrey Wilson, came to Sheffield in 1971 and called an informalmeeting of all the Sheffield community leaders. This was held in the new Grosvenor Hotel on Charter Square and about thirty community leaders turned up. I stood up at that meeting and, with some passion, explained what the situation was like for new immigrants from southern Asia. As a result I was invited on to the Conciliation Committee thatmet in Leeds and dealt with issues around the Yorkshire and Humberside region. In 1971, through the Conciliation Committee, which was chaired by Lord Boyle (who as Edward Boyle had been a respected Conservative Education Minister in the Sixties) I got to know senior civil servants and built up a useful network of contacts that I could use for the benefit of our Pakistani community in Sheffield.

Representing my community

Because of my membership of these official bodies, and my active role in the Pakistan Muslim Welfare Association (who had made me their Vice-President), I was acquiring a reputation among the Pakistani community of the east end of Sheffield as someone who had a bit of influence and could help people with their problems. In 1973 I was asked to go on the Industrial Tribunal as well and I was then in a position to help people who had been victimised at work and sacked. In dealing with other people my precept always was that I had “three friends”. They were “Trust, Affection and Understanding”. If you could achieve these with an individual then you would have a friend for life. Similarly, the same three rules could apply for relations between groups of people such as different ethnic groups and nationalities. Such an approach was far better than allowing mutual hostility to build up and fester, until, like a tightly depressed spring that finally snaps and springs up, the victims of abuse rise up and revolt. This would be no advantage to anyone, especially to the working class Pakistanis of Sheffield who only wanted to build a better life for themselves in Britain and were prepared to work all hours to achieve it.

It was therefore important to make sure that mutual respect was

established between the different ethnic communities in the city. When, in

1971, I was approached by a member of the Asian community who worked at

Laycocks on Archer Road, alleging that he had suffered constant racial abuse,

I went to see George Caborn, the full time District Organiser of the AEU.

George was a legend in the Sheffield Trade Union movement and, although a

dedicated member of the Communist Party, he worked closely with Labour

Councillors and members. I already knew that he had a cast-iron record of

opposition to racism, but he seemed reluctant to believe this case at Laycocks.

I was surprised and told him bluntly that my confidence in him had been

shattered, so he agreed to come to Laycocks with me and investigate. His

white members at the factory refused to admit that they had been racially

abusing this Asian man, but I literally had a trump card that I now played. I

pulled out a playing card and said dramatically; “I do not play cards myself but

I am holding a card which I will now play.” They all regarded me intently as

I turned over this playing card on which someone had scrawled “Paki

Bastard”.

It was therefore important to make sure that mutual respect was

established between the different ethnic communities in the city. When, in

1971, I was approached by a member of the Asian community who worked at

Laycocks on Archer Road, alleging that he had suffered constant racial abuse,

I went to see George Caborn, the full time District Organiser of the AEU.

George was a legend in the Sheffield Trade Union movement and, although a

dedicated member of the Communist Party, he worked closely with Labour

Councillors and members. I already knew that he had a cast-iron record of

opposition to racism, but he seemed reluctant to believe this case at Laycocks.

I was surprised and told him bluntly that my confidence in him had been

shattered, so he agreed to come to Laycocks with me and investigate. His

white members at the factory refused to admit that they had been racially

abusing this Asian man, but I literally had a trump card that I now played. I

pulled out a playing card and said dramatically; “I do not play cards myself but

I am holding a card which I will now play.” They all regarded me intently as

I turned over this playing card on which someone had scrawled “Paki

Bastard”.

George was shocked and tore into his members. In no uncertain terms he demanded that there would be no more of this racism among members of his union at this or any other factory in Sheffield. It was good to have people like George genuinely on your side, positively working for good inter-community relations and not just paying lip service to it as sometimes happened elsewhere. It was one of the reasons why Sheffield has had much more racial harmony over the years than some other industrial cities and towns. This did not happen by accident. People in both communities helped to make it happen, like George’s son, Richard, who became an MEP, then an MP and eventually a Government Minister, and Vernon Thornes, the full time Labour Party Agent. Among the Pakistani community in Sheffield, Nazir Haji Mohammed OBE from Rawalpindi, who lives in Nether Edge and was a City Councillor from 1995-2004, Qurban Hussein from Mirpur, who became Sheffield’s first ever Asian Lord Mayor in 1993, and Akhter Kayani, also from Mirpur, the founder of the Asian Welfare Association, along with many others, worked for co-operation and the building of bridges between the English and Asian communities in the city.

Another issue for which we tried to get a fair resolution, was the request for time off for Muslim Transport Workers to celebrate Eid, which was eventually granted by the City Council, although when it was first raised it was

rejected. We also had a case of prejudice against Pakistani taxi drivers at Sheffield’s Midland Station. The older taxi drivers were English and they guarded their priority right to park under cover on the station forecourt, where, of course, they got a regular supply of passengers coming off the trains. They argued that this was their right as they were the longest serving, but this unwritten rule just happened to discriminate against Pakistani drivers who, of course, had been driving in Sheffield for a shorter time. The complaint had been laid by Javid Khan and I helped to investigate, along with other members of the Conciliation Committee of the Race Relations Board, who came down from Leeds to meet Javid Khan and the Taxi Owners Association. We got an agreement that the priority on the station forecourt would be on the basis of everyone queuing to take their turn, not on how senior you were, which everyone knew was a racist excuse. It showed our community that the official institutions could work fairly, and that also helped the give and take between newcomers from Commonwealth countries and English workers and residents. Ironically, in Sheffield today virtually all the Hackney Carriage taxis are driven by Asian drivers, while the pick-up at the Midland Station has become a nightmare for all drivers, because of major refurbishment incorporating the enlargement of the passenger facilities into the old forecourt.

Pakistan leaves the Commonwealth 1972

When Pakistan was defeated in the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War and Bangladesh was established as an independent state, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the new Pakistani President, was so disgusted with the lack of support that the nations of the Commonwealth had given Pakistan, that in 1972 he withdrew Pakistan from the Commonwealth. This might have been a necessary, political move, that was popular for the moment in the Punjab and Sindh but it put thousands of Pakistanis in Britain into a position of grave uncertainty. Overnight they had become aliens in the UK and the British Government moved fairly quickly to rectify the position to help its Pakistani residents by the Pakistan Act of 1973. This decision of Heath’s Conservative Government, to give all Pakistanis in Britain the same rights that they had enjoyed pre-1972, was the correct decision, but it did not please the right wing of his Party. Perhaps to appease them it did not apply to the people like me from Azad Kashmir.

Our Pakistani passports did not confer on us full Pakistani citizenship, only including the phrase “former native of Jammu Kashmir”. It had not mattered before, because whether Azad Kashmir was recognised in international law as Indian or Pakistani, everyone was in the Commonwealth. Now they were not; and legally Kashmiri people were stateless and therefore aliens in Britain. This meant they could not vote and it also meant that it would be easier to deport them for minor offences or if they were unemployed. Moreover, if they left the country on holiday, or to visit their homeland, they might not be able to get back into Britain.

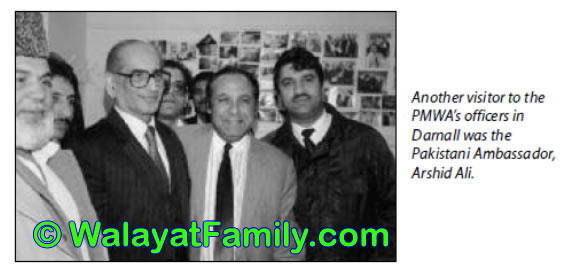

I organised a campaign that started in Sheffield but became a national one, to give Kashmiris from Azad Kashmir the same rights in Britain that other Pakistanis had now had restored to them. We organised demonstrations in London, held meetings, got signatures on petitions, made representations to the Pakistan High Commissioner – the Ambassador now – as well as putting our case to David Lane, a Junior Minister in Heath’s Government. The Conservative Government was unmoved but they were defeated in the Committee Stage of the Bill by the Labour Opposition, supported by four Conservative rebels. This amendment was not overturned at the Report Stage and so we gained the same rights as other Pakistani citizens. One of the Tory rebels was something of a surprise. It was Enoch Powell, who was opposed to the Pakistan Bill itself, as you might expect, because he regarded it as “unduly, unwisely and dangerously generous” but even he could see the absurdity of picking on the technicality of the Kashmiri’s unfortunate legal position and depriving them of their rights.

It had been a worrying incident because suddenly finding yourself officially stateless is a bizarre and unsettling experience. It made you feel very insecure even if Parliament, though not the British Government, had done the right thing by us in the end. If the Tory right wing had been in power, we might all have been shipped back to Kashmir and all we had achieved and worked for in Britain would have been lost. Such things did happen in Uganda in the Seventies, and in the Nineties there was “ethnic cleansing” of European Muslims in Bosnia and Kosovo.

Pakistan did rejoin the Commonwealth in 1989 but the precedent had been set. There was no such problem when Pakistan was suspended from the Commonwealth in 1999, when Musharaf came to power after a military coup. At the present time Pakistan is back as a member of the Commonwealth and has now re-established democratic rule. The Commonwealth is still regarded as a valuable international organisation by its 53 members and recently other countries have joined the Commonwealth, such as Mozambique and Rwanda, who were never part of the British Empire. Presumably they, like Pakistan, obviously see some benefit in being members of this, really rather unusual, international organisation.

Not elected

In 1974 I stood for the position of shop steward in my branch of the TGWU. I was up against a long serving shop steward, Ken Sheldon, who was well respected, but many Asian drivers and conductors believed I could do a better job. By now there were a lot of Asian bus drivers and conductors on Sheffield’s buses and they mobilised their support for me, giving up time and losing pay to go and vote. It was a very close run thing and in the end they said I had lost by only one vote, and I do not think any of the English members voted for me. So, it seemed to us that getting elected to positions of responsibility was going to be much more difficult than just getting our problems sorted out, and perhaps race still played some part in the Labour Movement.

By Dr. Choudry M. Walayat MBE

Copyright 2009 - Dr. Choudry M. Walayat MBE

You May contact Choudry Walayat on his Mobile - 07941016417 (UK)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All rights reserved. No part of this online book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanised, by photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written consent.

Online Copy Published by Nadeem Walayat - Contact admin@REMOVEwalayatfamily.com

Hard Copy Published by Kashaf Walayat - ISBN Number 978-0-9560445-0-1 - Contact on Mob. No. 0044 7766 22 1006

All facts and opinions in this book are the sole responsibility of Dr. Choudry M. Walayat. The book has been written in co-operation with John Cornwell, who produced the final texts of the chapters of the book.